Leadership

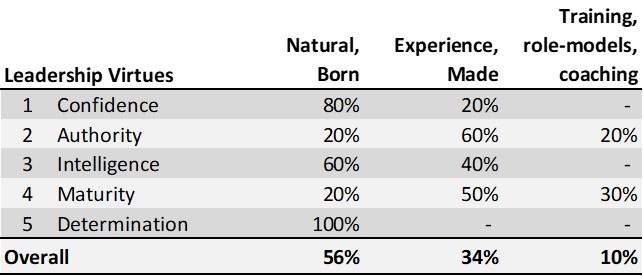

Leaders are 56% born, 34% made and 10% learned (see table below for calculation). The point is that a born leader may never rise for lack of opportunity. It also means we should forget the idea that we can all become leaders. We cannot. Leaders are a minority among us.

If we want to understand leadership, we need to peel away some of the outer layers of expectations that are projected on to the role of leaders. Leaders are not there to fulfil the potential of others or make people feel good about themselves. Neither do they need to be role models of good behaviour. These things are nice but obscure the true role of leadership. Leaders are there to get results; to achieve things.

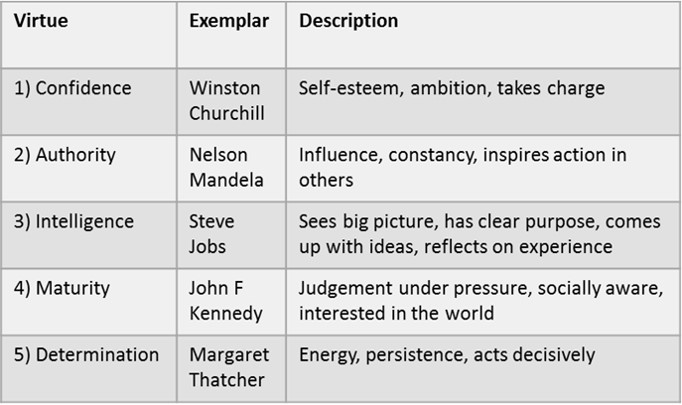

This tutorial strips leadership down to the bare essentials and considers five leadership character traits. Bear in mind that characteristics in the table below are innate to a person’s personality but can also develop with experience and, to a limited extent, can be learned.

Confidence

Many people fall at this first hurdle. Leadership involves being prominent, taking personal responsibility, and putting yourself forward. As a consequence, you will be the object of criticism, expectations of your performance are raised, and you put yourself under pressure. Most people find this uncomfortable. To cope well you need to have trust in yourself.

For some this comes naturally. I selected Winston Churchill as the exemplar of this virtue because, as a son of an aristocrat, the grandson of a duke and cabinet minister, he truly felt born to lead. As young man he told a dinner guest ‘We are all worms but I, perhaps, am a glow worm.’

Confidence is more than being a big-head. It can be learned. There is nothing more satisfying than taking on a task that others, including even yourself, think is difficult and succeeding. Confidence develops naturally from such experiences. Confidence is developed by deliberately challenging yourself and building a track record of success. If you are in a junior management position undertaking a special project – ideally that solves a problem for your boss – is a good place to start. Confidence is more nuanced than just being sure of yourself. It encapsulates ambition. This means never being entirely satisfied with what’s been achieved and wanting to better. And being prepared to take risks in doing so. Without this quality of ambition leaders are just managers that happen to occupy a leadership position.

Authority

As leaders spend much of their time telling others what to do, it becomes a bit of a problem if they don’t do what you ask. To get others to respond to your bidding, you need authority.

Authority comes in many guises, the most obvious being hierarchy. Hierarchical authority is easily gained and its deployment may not require much skill on the part of the leaders. At its most basic you’re asking someone to ‘do their job’. This type of leadership is effective not just because we all need the money a job brings, but because the alternative is anarchy. Even a detested leader is preferable to anarchy if they bring order. Leadership is benign dictatorship.

Many of the most effective leaders I’ve worked with wore their hierarchical power lightly. I found myself going an extra mile for them, not because they asked me, but because I wanted to. I wanted their good opinion, whether or not they had persuaded me of the merits of their goal. This type of respect and influence comes from the character of the leader. It accumulates and so grows with consistency of behaviour. It needs no hierarchy because it inspires.

I watched Bill Clinton with Nelson Mandela some years after they had both left office. Mandela said ‘Mr President’, and Clinton said to camera, ‘Oh my! Whenever I heard those words I knew that I was going to be asked for something that I was going to do, whether or not I wanted to do it’. That’s authority.

Intelligence

By a long way, the most important aspect of this leadership trait is being able to cope with complexity. Many analytically clever people fail this test of intelligence. This virtue requires the ability to ignore alternatives and follow instead one single path. It sounds like it should be easy until you see many academically intelligent people caught in the headlights of a complex, ambiguous, and uncertain situation with incomplete information. A normal business decision, in other words. Either they are so fazed they do nothing, or they take so long exploring the alternative options they take too long to make the decision. A leader brings clarity to these situations.

Being clear in your mind is not the same as being right. It does not need to be. Choosing a wrong path is less important than choosing a path in the first place because, if wrong, you can always take corrective action. This illustrates another strong feature of intelligence: learning from experience. Anyone can learn from books, not everyone learns from experience. Why? Sometimes we don’t search deeply enough if we are unlikely to like the answers we find. A leader will replay a bruising experience over again, often for years, searching for lessons to draw from it. They won’t forget it. They will reflect on it, wondering what they could have done differently.

Our egos have a bit of self-protective mechanism that saves us from becoming too melancholy when we’ve made mistakes or let ourselves down in any way. This is a good thing but it can prevent us from learning by being too quick to justify our own actions or projecting causes of failure on to others. A police driver once told me that even if an accident isn’t directly your fault, there are often ways in which you could have driven differently that might have avoided it. So it is when things go wrong in your career and in business. The intelligent person is honest with themselves.

It would be wrong to suggest that raw brain power is not also an important leadership virtue. It clearly is. The ability to analyse, to synthesise information of different types, to come up with new ideas. These are all aspects of intelligence. Leaders are always planning ahead. This requires creativity and imagination.

Maturity

A person’s maturity is tested under pressure. Pressure can come in the form of deadlines, expectations, conflict and unfamiliar circumstances. Under pressure the quality of our decision-making, even of our social behaviour, can suffer. Under sufficient pressure the immature mind breaks and becomes reactive, erratic and emotional. In this circumstance, no action is forthcoming because the broken leader is just flapping around.

I chose John F Kennedy as an exemplar of this virtue because there can be few more pressured situations than the Cuban missile crisis. Also because earlier in his presidency, during the disastrous US-sponsored invasion of Cuba at the Bay of Pigs, Kennedy didn’t shrink from taking responsibility.

Maturity as a leadership virtue encompasses awareness of how people work, which is necessary to function well within organisations. Such people have sensitive social and political antennae. It involves being interested in the world, looking outside the organisation, being able to put yourself in the mind of others, such as your customers, which is vital for developing strategy.

Maturity obviously involves behaving like an adult but it need not be age-dependent. We all know plenty of ‘kidults’ and no doubt also have also met plenty of young people wise beyond their years. However, maturity does tend to grow with age which is why this is the one area of leadership that responds best to coaching, and observing role-models.

Determination

It would be nice if a leader could sit in their boardroom receiving business proposals on which they make decisions while, inspired by their leader’s rhetoric, everyone else rushes off to make it happen. Nice, but unrealistic.

Business is a messy affair, difficult affair with frequent set-backs and unexpected headwinds. A certain bloody-minded doggedness is required to convert plans into action and then work out what to do when – inevitably – things go wrong. This is the unattractive part of a leader’s job. They will never be invited to Harvard to speak about how they kept buggering on. Nevertheless determination is a necessary virtue if you want anything done.

What does it require? Energy, more than anything else. Enthusiasm and optimism help. Different things drive different people but among the characteristics of determined people you will find a certain pride in doing a good job, a sense of pleasure in hard work, a desire not to fail, even a straightforward fear of failure.

I chose Margaret Thatcher to illustrate this virtue, knowing that she is a divisive figure for many. Determined leaders do not always win popularity contests. My reason however was because in 1981 she famously received a letter signed by 364 economists telling her she was on the wrong path. And she kept going.

If nothing else is required of leaders, they must at least act decisively and press for results. Given the hurdles they encounter, it requires a strong-minded person to keep going in adversity.

Leadership v Management

Business leaders are also, of course, managers. I have deliberately isolated only those traits that I think are specific to leadership. However, in so doing, I risk ignoring the management skills that you would ideally want of any business leader. These are the ability to plan, organise, monitor and motivate. It is the last of these, motivation, that is most frequently described as a leadership skill. It certainly takes skill but many successful leaders are poor people managers so, strictly, I don’t think can be a necessary one.

Born, Made or Coached

Whether leaders are born, made or coached is clearly important for companies wishing to recruitment, recognise and advance the most promising leaders in their organisation. The table below suggests the degree to which each leadership virtue is innate, developed with experience or learned through formal training, coaching or simple observation of role models. Assuming each virtue is equally important an overall ranking is suggested. Obviously subjective, it nevertheless feels about right based on my experience.

What are the implications for leadership development of this analysis? Firstly, that companies try to identify born leaders during their recruitment. Secondly, potential leaders should be given challenging experiences as early in their career as possible. Thirdly, from mid-career onwards, the focus should be on coaching them and letting them work with inspiring role-models.

You’d find no argument from any HR manager with this prescription, but only the highest performing companies take these last two actions seriously. It’s a shame because once a potential leader has solid experience and a bit of career momentum behind them, mentoring is probably the only development tool left available to companies to help their aspiring leaders, and there’s still room for quite a bit of leadership growth to be accessed.

If you’re a born leader, but lack the opportunities or role models, you are unlikely to fulfil your potential. For any aspiring leaders that find themselves stuck with a bad boss or an unambitious employer it means there is only one course of action left to them: leave.